Center for Teaching & Learning

Creating Passionate Readers - A Piece by Nancie Atwell –

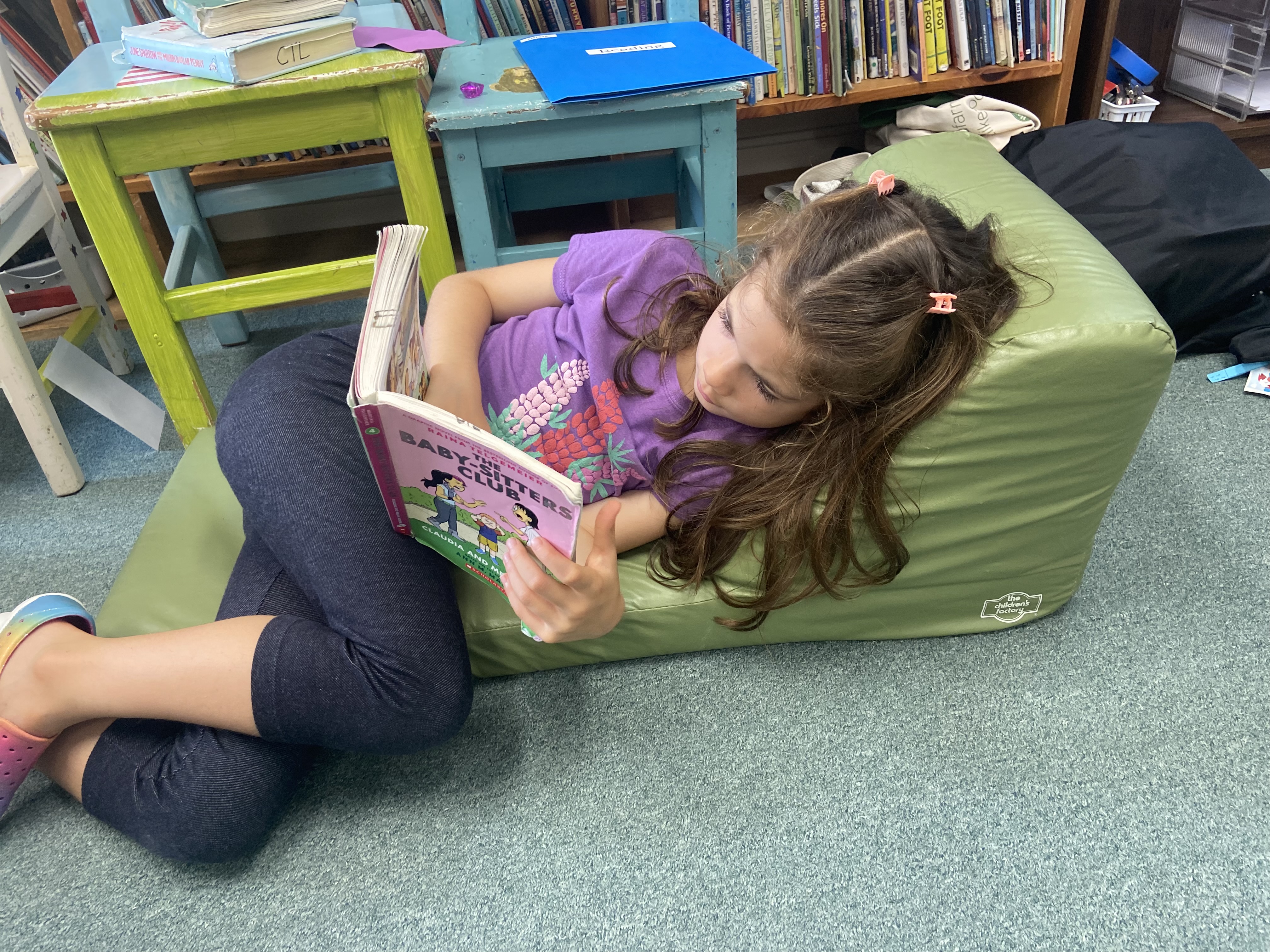

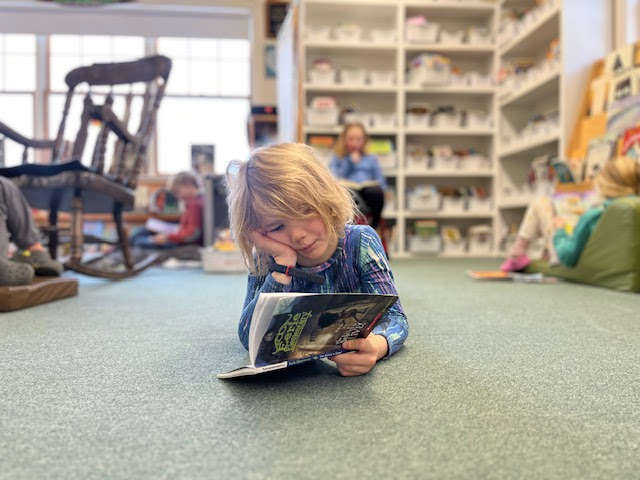

The annual average number of books read by seventh and eighth grade readers at CTL is at least forty titles. In the lower grades, the numbers are similarly high. My K-6 colleagues and I make time every day for our students to curl up with good books and engage in the single activity that consistently correlates with high levels of performance on standardized tests of reading ability. That is frequent, voluminous, self-selected reading. A child sitting in a quiet room with a good book isn’t a flashy or marketable teaching method. It just happens to be the only way anyone ever became a reader.

Our goal is for every child to become a skilled, passionate, habitual, critical reader—as novelist Robertson Davies put it, to learn how to make of reading “a personal art.” Along the way, CTL teachers hope our students will become smarter, happier, more just, and more compassionate people because of the worlds they experience within those hundreds of thousands of lines of print.

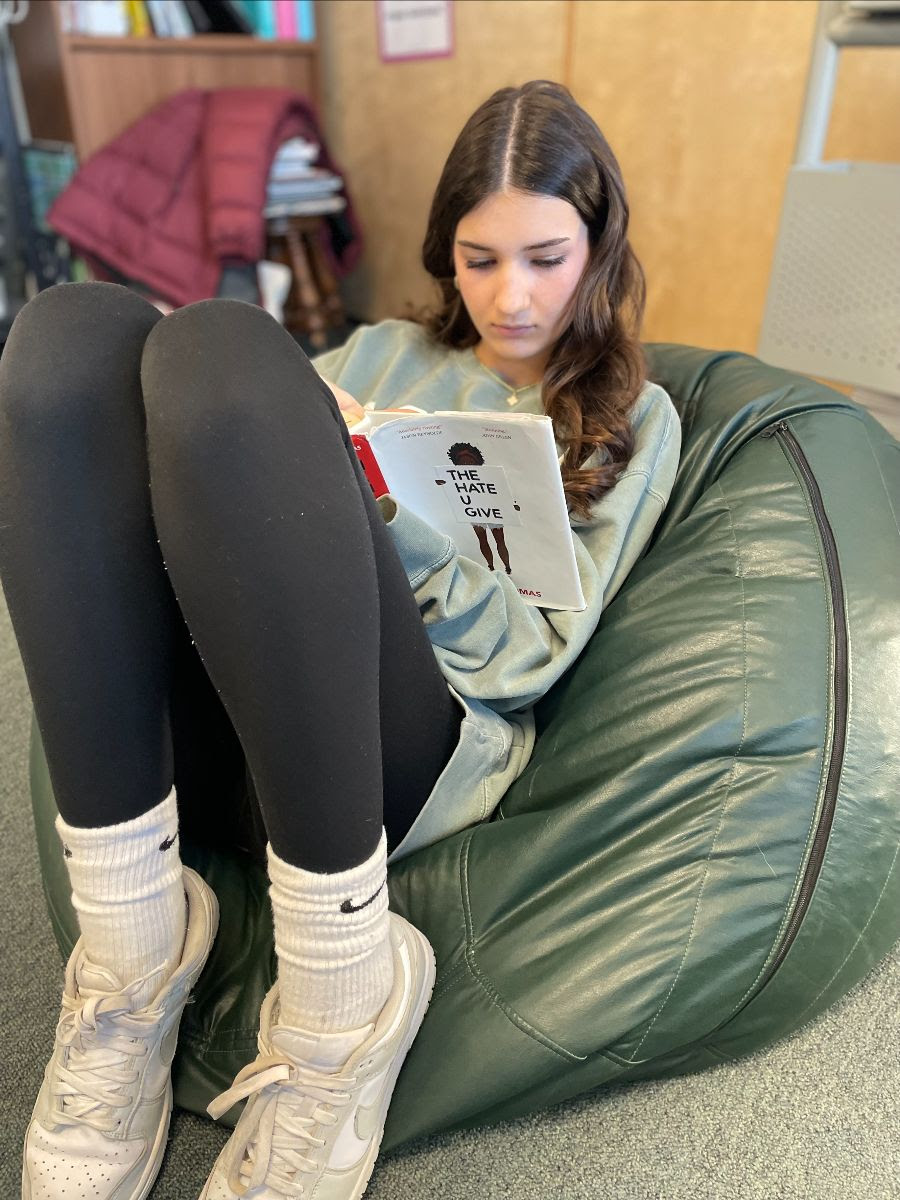

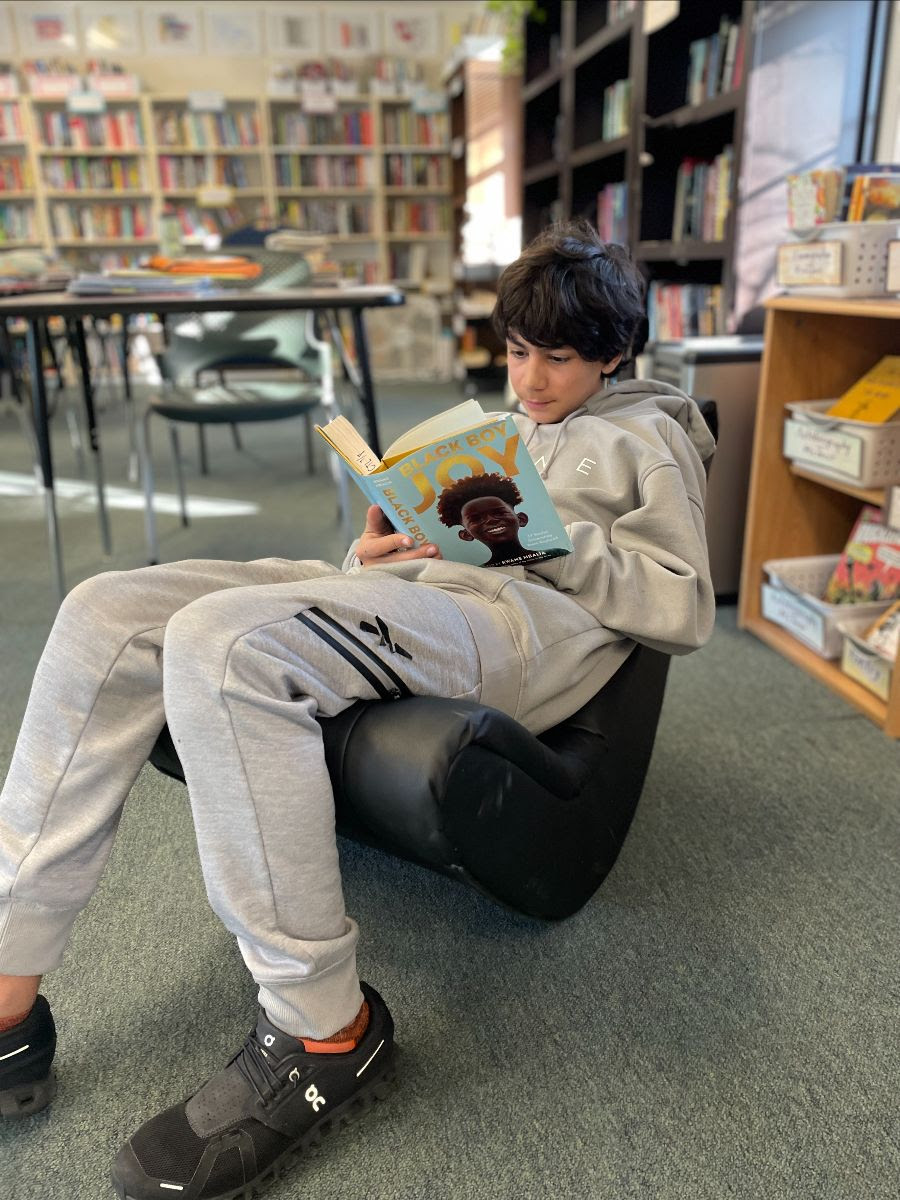

We know that students need time to read, at school and home, every day. We understand that when particular children love their particular books, reading is more likely to happen during the time set aside for it. And we have learned that the only sure-fire way to induce a love of books is to invite students to select their own. CTL teachers buy the best children’s literature we can find, conduct booktalks and bookwalks, and help our students choose books, develop and refine literary criteria, and carve out identities for themselves as readers. We get that it’s essential for every child to be able to say These are my favorite books, authors, genres, and characters this year, and this is why. Personal preference is the foundation, walls, and ceiling in building a reader for a lifetime.

Starting in kindergarten, free choice of books is a child’s right, not a privilege granted by a kind teacher. Our students have demonstrated that opportunities to consider, select, and reconsider books make reading feel sensible and attractive to children right from the start-that they’ll read more books than we dreamed possible and more challenging books than we dreamed of assigning them.

We’ve also learned that students need access to a wide, up-to-date assortment of inviting titles. Instead of investing in class sets of novels or expensive basals or anthologies, we make classroom libraries of individual titles our budget priority. Teachers read a lot of the books that we hope our students will, so we can make knowledgeable recommendations. We offer help when readers need it, and we teach children, one at a time, about books and reading in the daily, quiet conversations in our reading workshops.

We understand that the only delivery system for reading comprehension is reading. When reading is meaning-filled, understanding cannot be separated from decoding. Reading comprehension is not a set of sub-skills or strategies that children need to be taught to bring to bear once they’ve learned to translate letters to sounds. When students are reading stories that are interesting to them, and when the books are written at their independent reading level, comprehension—the making of meaning—is direct, and kids understand.

Human beings are wired to understand. As reading theorist Frank Smith put it, “Children know how to comprehend, provided they are in a situation that has the possibility of making sense to them” (1997). Reading workshop is our best approximation of an instructional context that has the possibility of making sense to young readers: a child sits in a quiet, book-filled space, engrossed in a beloved book in the company of classmates who are reading and loving books, too, monitored by a teacher who knows about literature, reading, and his or her students’ tastes, strengths, and challenges.

Because CTL is a non-profit demonstration school, a place where other teachers come to learn about innovative methods, we work hard to attract a student body that represents a diverse range of socioeconomic backgrounds and ability levels, and we fundraise twelve months a year so we can set a tuition rate that’s as low as possible. The goal is to attract a mix of students in whom visiting teachers can recognize their own.

And they do, because CTL students are regular kids. They are diagnosed with ADHD and such identified learning disabilities as nonverbal learning disorders, visual processing difficulties, and dyslexia. Some kids come from homes with packed bookshelves; others own only a few books. Maine is a rural state and a poor one, in the bottom third nationally in terms of per capita income. Only 66% of jobs here pay a livable wage, and our students’ parents work hard at all kinds of occupations: farmer, carpenter, house cleaner, store clerk, soldier, fisherman, gardener, postal worker, and housecleaner, as well as physician, minister, teacher, and small-business owner.

We do not believe that CTL students’ accomplishments as readers can be explained away as an anomaly. Ours is not a privileged population of students. This is what is possible for children as readers.

It’s also important to understand that reading workshop is not S.S.R. (Sustained Silent Reading). It’s not a study hall, where we watch the clock with one eye as we Drop Everything And Read. In reading workshop, we teach readers for a lifetime: introduce new books and old favorites, tell about authors and genres, read aloud, talk with kids about their reading rituals and plans, and present lessons about elements of fiction, how poems work, what efficient readers do—and don’t do—when they come across an unfamiliar word, how punctuation gives voice to reading, when to speed up or slow down, who won this year’s Newbery Award, how to keep a reading record, what a sequel is, what readers can glean from a copyright page, how to identify the narrative voice or tone of a novel and why it matters, how there are different purposes for reading that affect a reader’s style and pace, how to unpack a poem, how to distinguish between popular and literary fiction, how to tell if a book is too hard, too easy, or just right, and why the only way to become a strong, fluent reader is to read often and a lot.

Reading workshop is one of the simplest and hardest things we do. It’s also the most worthwhile. Students leave our school as literary, well-above-grade-level readers. But they also leave smarter about a diversity of words, ideas, events, people, and places. Books and stories bring the whole world to a tiny school in rural Maine. When the readers grow up and leave the school, they recognize the wide world they encounter out there because it is already lodged in the “chambers of their imaginations” (Spufford, 2002).

Sydney Jourard wrote, “The vicarious experience of reading can shape our essence, change us, just as firsthand experience can. Experience seems to be as transfusible as blood” (1971). For students who know reading as a personal art, every day is a transfusion. Every day they engage with literature that enables them to know things, feel things, imagine things, hope for things, become people they never could have dreamed without the transforming power of books, books, books.

Three times a year, the boys and girls at CTL help their teachers create master lists of the inviting, accessible books they love best. The “Kids Recommend” lists feature the titles our students name in response to this question: Which books do you love so much that you think they might convince a _____-grader—someone who’s a lot like you, except that they don’t read much—that books are great? The answers are available to our students and their parents, as well as other teachers, their students, and the general public here on our website.

Students update the lists continuously, because the field of children’s literature changes so quickly. While a handful of titles do maintain their popularity—S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1968), the novel that virtually created the field of young adult literature, continues to speak to middle schoolers—many drop off and are replaced over time.

We hope CTL’s book lists set a trend. Our goal is a national network of websites of great titles, nominated by K-12 students from all kinds of school settings who choose their own books: favorite titles of a cross-section of American children as the go-to resource for teachers selecting literature for classroom libraries in diverse communities.

If you are interested in learning more about how we teach reading at CTL, with former CTL teacher Anne Merkel, I have co-written a brief, practical book for teachers and parents entitled The Reading Zone: How to Help Kids Become Skilled, Passionate, Habitual, Critical Readers (Scholastic, 2016, second edition); an overview of CTL’s entire program, Systems to Transform Your Classroom and School (Heinemann, 2014); and a third edition of In the Middle: A Lifetime of Learning about Writing, Reading, and Adolescents (Heinemann, 2015).

With all best wishes,

Nancie Atwell